(Dan Tri) – Each time she crossed steep mountain slopes in the freezing night to deliver a baby, physician Lò Thị Thanh would quietly remind herself: "If I give up too, how can I expect the community to change?"

Only three days into her assignment at the Mu Sang Commune Health Station (Phong Tho District, Lai Chau Province), physician Lò Thị Thanh (46, originally from Dien Bien) was already called into the village for a delivery. It was a critical case—a mother with a retained placenta.

“The roads weren’t paved back then. It was all steep, slippery slopes. Her family had to ride a motorbike out to get me,” Thanh recalls vividly of that day in 2007.

The motorbike skidded down the slope, as if it were plunging into a ravine. When she finally arrived, Thanh exhaled deeply and whispered with trembling voice: “Mother, I’m still alive.”

In Mu Sang, many women still choose to give birth at home. To them, childbirth is strictly a matter between women—a domestic affair, with no need for health workers. They believe that if a baby is born where their mother once gave birth, that child will enter the world safely too.

But thanks to Thanh’s unwavering commitment, that mindset is slowly shifting. Women who once hesitated at the sight of a white coat now call out confidently, “Ms. Thanh, I’m having contractions.” Husbands, who once saw childbirth as “women’s business,” now sit quietly outside the commune clinic, waiting for their wives to give birth.

"If I give up too, how can I expect the community to change?" — for the past 18 years, that question has kept this woman rooted in the highlands, dedicating her life to each safe delivery and every heartbeat of change.

01. Children Born on Wooden Planks in Makeshift Homes

"Sometimes a family member runs over to call me: ‘Ms. Thanh, someone in Sin Chai village is in labor,’” says physician Lò Thị Thanh, beginning her story with a humble tone.

Over 20 years ago, Thanh graduated with a degree in obstetric medicine in Dien Bien. She was then assigned to work at the health station in Mu Sang Commune.

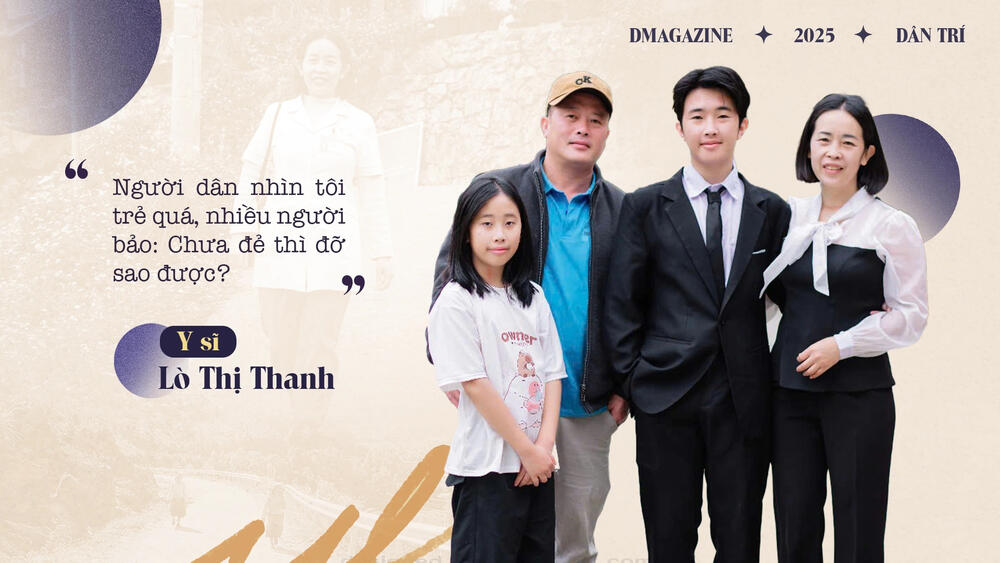

Back then, she was just in her early twenties—shy, unfamiliar with the local customs and terrain. “The villagers thought I was too young. Many said, ‘You’ve never given birth—how can you help others deliver?’” Thanh recalls.

The journey from Mu Sang’s center to the furthest village stretches 15 kilometers across slick, rocky slopes—treacherous even without the added challenges of rainy season floods. Often, it’s not just a trek over terrain, but a race against life and death.

Mu Sang Commune lies nearly 40 km from the district center, with 99% of the population belonging to ethnic minority groups.

Here, home births were once as routine as starting a fire to cook rice. No doctor, no midwife, no medicine or equipment—just a wooden house with a plank bed, and a family member—often the mother-in-law or an older sister—standing nearby.

Ma Thi My, now 85, from Han Sung village, shares:

“I gave birth to ten children, all at home. I never went to the health station, never got advice. Back then we didn’t know what a doctor was, and we didn’t even call the shaman. Some were lucky, but many lost their babies—some lost both mother and child.”

Her voice softens:

“All we knew was to eat what the customs allowed, whatever we had. It was a hard life.”

The lack of information, coupled with deeply rooted cultural beliefs, once made childbirth in the highlands a lonely and dangerous journey.

"The villagers thought I was too young. Many said, ‘You’ve never given birth—how can you help others deliver?’" – Physician Lò Thị Thanh.

02. "If I gave up too, how could I expect the community to change?" – Physician Lò Thị Thanh

Deeply entrenched customs and lack of awareness once made healthcare seem distant—at times, even frightening—for many villagers.

Being a midwife in Mù Sang isn’t just about medical skills. It means knocking on every household’s door, finding ways to cross cultural boundaries.

Over her long journey, certain births remain etched in Thanh’s memory as if they happened just yesterday. One case she remembers vividly was a woman giving birth for the third time—one of four deliveries she would assist.

During that third pregnancy, Thanh didn’t just provide regular checkups. She called often to check in: “Are you transplanting the fields today? Any signs of contractions?”

If the family had no phone, she would trek out to them just to say again, “If anything feels unusual, go straight to the clinic.”

Still, that night at 2 a.m., the husband came rushing to report, “My wife gave birth 30 minutes ago.”

Thanh was stunned. Just that morning she had reminded them carefully about what to do.

“They said the road was too difficult to bring her,” Thanh recalls. That has always troubled her—even with all the precautions, Mù Sang is a place that’s not easy to reach.

The woman suffered from placenta accreta, a serious obstetric complication that can cause life-threatening bleeding if not treated quickly. Thankfully, Thanh arrived just in time.

In the days that followed, she continued visiting the mother, checking for signs of postpartum fever or complications.

“If they won’t come to me, then I’ll go to them,” Thanh says. “Here, people in the village can take offense easily. So I just gently say: ‘You see, it’s lucky this time was manageable. If it had been worse, we’d have needed to transfer her to the district or even the provincial hospital.’”

Had she not arrived in time that night, the woman would have been sent straight to Phong Thổ District Hospital—where surgery would have been the only option.

But to ethnic communities in the highlands, surgery remains something foreign, even frightening.

That same family came to her again for their fourth delivery—but this time, they came on their own. No convincing needed

“They called me when the contractions began. I said, ‘Come to the clinic—I’ll help.’ And they did. I was so happy. Suddenly, it all felt worth it,” Thanh says, smiling.

That joy didn’t come overnight.

When she first arrived in Mù Sang, Thanh felt like she was facing an invisible wall. Not the steep hills or stormy nights—but the hardest barrier of all: language.

The villagers spoke Hmong. Thanh, an ethnic Thai, felt like a stranger every time she entered a village. She didn’t understand them, and she didn’t know how to speak in a way they would trust or understand.

So she began to teach herself—no books, no classes. Her classroom was the fireside, the market paths, the fields.

Pointing to a roadside plant, she’d ask, “What do you call this in Hmong?”

Listening to women complain of pain, she paid attention to every word, every expression—guessing, learning. She memorized the names of herbs, how to describe abdominal cramps in Hmong, and how to speak gently enough not to embarrass them.

“If I don’t understand their language, how can I understand their fears and worries?” Thanh asks.

In her view, working with communities takes more than expertise. It requires compassion. And sometimes, that begins with simply learning how to name a local plant the way villagers do.

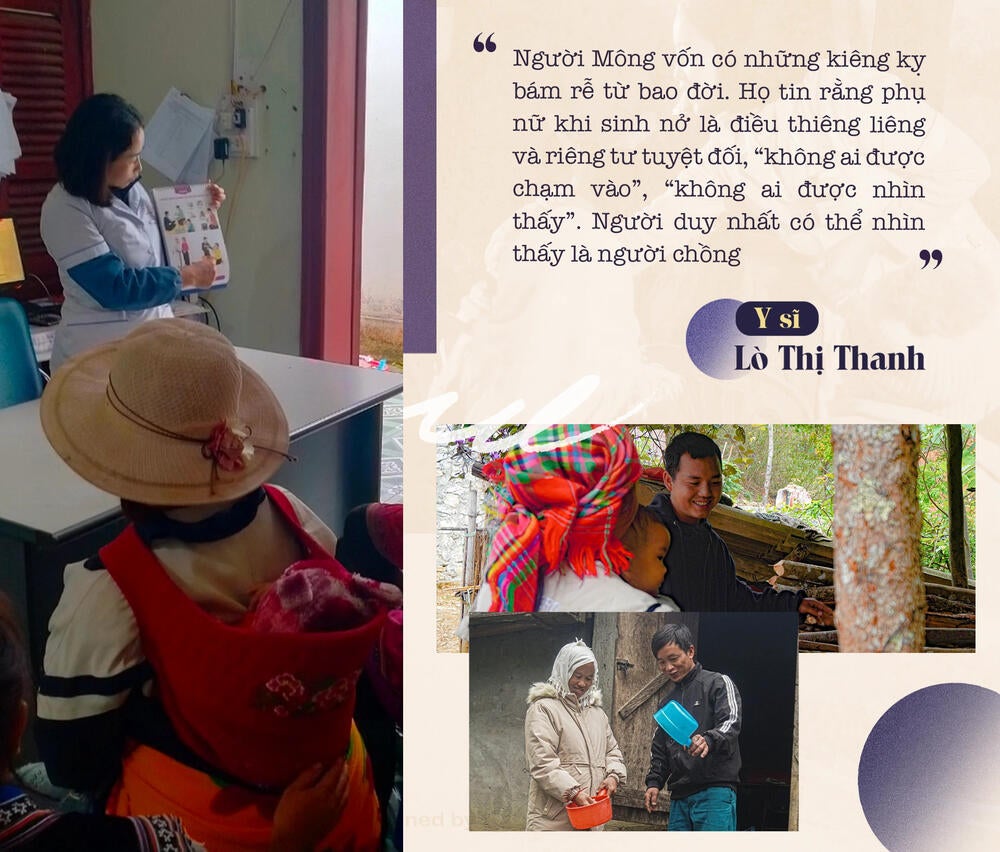

But even after overcoming language, Thanh faced what she says is the toughest challenge of all: ancient customs. Unseen barriers, but deeply rooted in every thought and daily rhythm of life in the highlands.

“Hmong people have taboos passed down for generations. They believe childbirth is sacred and deeply private—‘no one must touch,’ ‘no one must see.’ The only one allowed is the husband,” she explains.

And so, for generations, mothers here have been giving birth alone in cold homes, cutting the umbilical cord with knives or sickles.

Prenatal checkups and gynecological visits were unfamiliar, often uncomfortable. “Many women would come in and shyly ask, ‘Is Ms. Thanh here?’” she says.

Even the best doctors at the district hospital couldn’t gain their trust. But Ms. Thanh—whom they considered family—was close enough for them to open up to. Because Thanh doesn’t just understand medicine. She knows every home, every path they walk.

“If I don’t understand their language, how can I understand the fear they carry?

03. "More than once, I wanted to pack everything and return home."

Life is a canvas not only filled with bright colors. There have been many times when Physician Lò Thị Thanh wanted to pack her things and return to her hometown.

Those moments when she "took a gamble" accompanying a pregnant woman on a stretcher up steep mountain slopes—tired and terrified—she would think to herself: Maybe it’s time to stop…

Up here, her husband is a teacher, but their two children remain back home with their grandparents. She only manages to visit every two to three months.

There were times her husband said to her: “Why do you keep throwing yourself into this? Getting up in the middle of the night to rush out—no one’s giving you any medals for it.”

Recalling those mental battles with herself, Thanh falls silent for a moment.

“When your husband said those things, when you remembered the moments you thought you couldn’t go on anymore—what made you stay here all these 18 years?” the reporter asks.

Thanh replies slowly, as if speaking to her own heart:

“Their lives are like that—quiet, lacking, and full of endurance. If I give up, if I turn away too, then how am I any different from the hardship they’ve known all along? I can’t expect them to change if I’m not willing to stay the course myself.”

She knows her husband loves her. She knows her family needs her. But she just can’t walk away. Every time she sees the anxious eyes of a first-time mother, or feels a trembling hand clutch her coat in pain late at night… she simply can’t bring herself to leave.

“The Hmong people have long-held beliefs passed down through generations. They believe childbirth is sacred and entirely private—‘no one is allowed to touch,’ ‘no one is allowed to see.’ The only person allowed to see is the husband.” — Physician Lò Thị Thanh

04. A New Generation of Mù Sang — Born and Raised in Health

Challenges remain: scattered households in remote terrain, nighttime dangers, language barriers, and customs that resist change. But hope is rising: younger generations now finish 9th grade, women are becoming more confident, and children are growing up strong — thanks to the hands of Midwife Thanh who delivered them into the world.

Today, nearly 70% of pregnant women in the commune attend regular antenatal checkups.

Concepts once unfamiliar — “ultrasound,” “iron supplements,” “first trimester checkups” — are now common in conversations around kitchen fires and at the village gate. Since Midwife Thanh began her work at the health station, Mù Sang has not recorded a single maternal death.

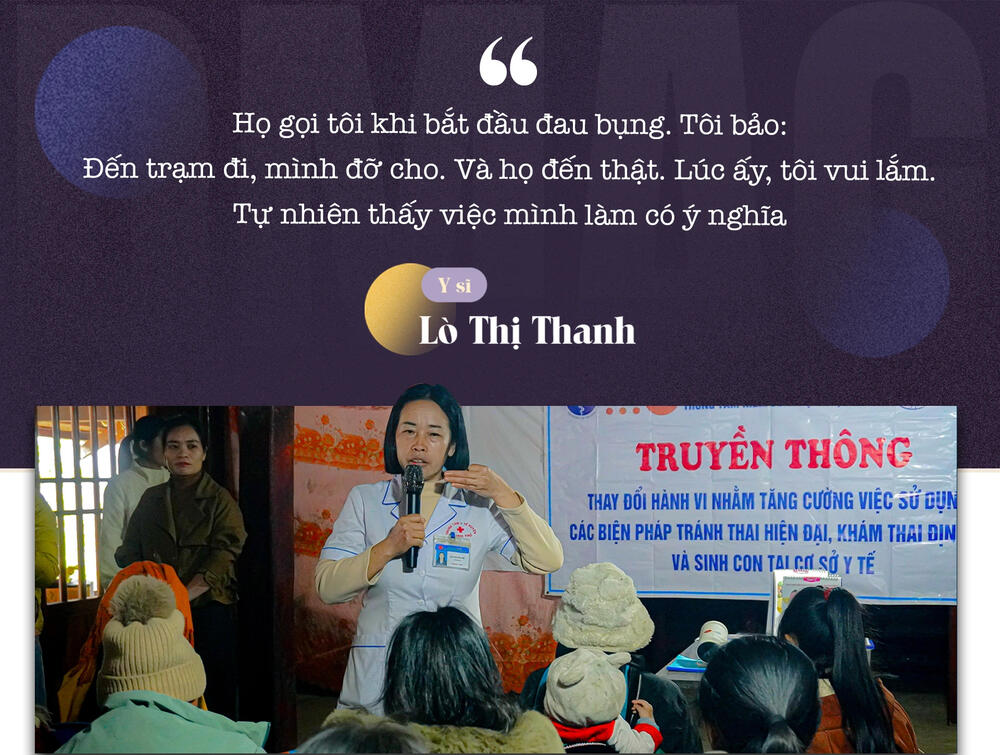

Beyond her role in prenatal care and delivery, she regularly organizes small community sessions at the village cultural house — sessions that locals fondly call “Ms. Thanh’s awareness meetings.”

There, she teaches about prenatal nutrition, warning signs in pregnancy, and newborn hygiene. At first, many women came only out of obligation. But gradually, they began to ask questions, to truly listen.

Encouragingly, it’s not just the women who have changed. The men — once believing childbirth was solely “a woman’s matter” — are beginning to show interest.

Mr. Ma A Phứ (35), a resident of Sin Chải village, is one of them. In 2010, his wife gave birth safely at the health station, thanks to Midwife Thanh’s patient persuasion. Fifteen years later, when they found out they were expecting again, the couple didn’t hesitate:

“Just like last time, we’re counting on Ms. Thanh,” Phứ shared.

Ever since, he’s attended every awareness session.

“Sometimes the other men are busy and can’t join, so they ask me afterward: ‘What did Ms. Thanh teach today?’” he recalled.

“When men begin to care about childbirth, I know there’s hope,” Midwife Thanh said with a smile.

Giàng A Lùng (22) and his wife, once hesitant and fearful, have also changed. Their first child was born at home — just as their elders had done for generations.

“We were nervous, but since our parents and grandparents had always delivered at home, we did too,” Lùng admitted.

“Home births were unhygienic, but back then we weren’t informed. Many families avoided the health station thinking it would cost too much.”

Sometimes, change begins with a simple moment: a mother hearing her baby’s heartbeat for the first time through a fetal monitor, a newborn placed on a clean bed with trained medical staff by their side.

These moments may seem small, but in Mù Sang, they represent a journey through forests, over mountains, and beyond generations of ingrained beliefs.

Still, not all villages have crossed the threshold. In some areas, child marriage and early childbirth persist as deeply rooted practices.

Giàng Thị Su (18), from Sin Chải, is one such case. She married right after finishing 9th grade — just 16 years old.

Fortunately, she met Midwife Thanh. Su received proper counseling and prenatal care, and was transferred to the district health center to deliver safely. Hers is just one of many similar stories Thanh has seen.

“Despite years of awareness-raising, child marriage still accounts for up to 20%,” said Đào Hồng Nhật, Head of Mù Sang Commune Health Station.

According to Phàn A Chinh, Chairman of the Mù Sang People’s Committee, this remains one of the most persistent challenges, despite continuous efforts by local authorities to educate and advocate for change

05. The Midwife of Mù Sang

The people of the village call medical officer Thanh “the midwife of Mù Sang.”

For 18 years, she has never missed a single call, never turned down a single birth. Ms. Lò Thị Thanh is not just a community midwife — she is the one who has carried the hopes, and shifted the mindset, of an entire generation of ethnic minorities in this remote borderland of Viet Nam.

Though there is still much left to be done, Ms. Thanh continues her work — quietly and steadfastly.

In the mountains of Mù Sang, where life and death may be separated by a single steep road, there lives a woman who chose to stay.

According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), maternal mortality in mountainous and ethnic minority areas is two to three times higher than the national average — ranging from 100 to 150 deaths per 100,000 live births. H’Mông women, in particular, face a maternal mortality risk seven times higher than that of Kinh women.

A report by the Lai Châu Provincial Department of Health on maternal and child health services (2022–2024) confirms that the maternal mortality rate remains high in ethnic minority communities.

Ms. Trần Thị Bích Loan, Deputy Director General of the Ministry of Health’s Department of Maternal and Child Health, noted that changing long-standing customs and beliefs among local people will take time.

“Our limitations in infrastructure and health workforce make it difficult to consistently deliver quality services to ethnic minorities. This gap contributes to missed opportunities for antenatal screening, early diagnosis of obstetric complications, and the prevention of maternal deaths,” Ms. Loan said.

She emphasized that alongside the state budget, international cooperation is a key solution — enabling greater access to medical equipment and financial resources in underserved mountainous provinces.

The project “Leaving No One Behind: Innovative Interventions to Reduce Maternal Mortality in Ethnic Minority Areas of Viet Nam,” jointly implemented by the Ministry of Health, UNFPA, and MSD, aims to do exactly that.

In Mù Sang commune (Phong Thổ district, Lai Châu), the project has already helped increase the proportion of facility-based deliveries from 24% in 2022 to 61% in 2024, and routine antenatal care coverage from 27.2% to 41.7%

Credit: Dân Trí

Content: Linh Chi, Minh Nhật

Photography: Linh Chi

Design: Huy Phạm